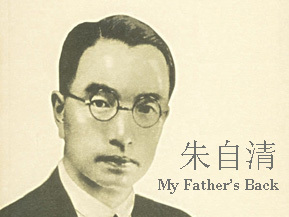

When we called modern Chinese literature depressing we weren't kidding. Our romp through the canon to date has touched on the emotions of indifference, grief, helplessness and shame. To this we now add Zhu Ziqing's guilt-laden reflections on filial inadequacy.Written in October 1925, this short essay chronicles Zhu's relationship with his father, a self-made man who ended up trapped between his son's high expectations and his own perilous finances. This classic story remains widely read in high schools throughout China, as well as in many university programs on Chinese, where it is typically assigned to third or fourth year students. Although My Father's Back has the occasionally antiquated turn of phrase (as noted in our manually annotated popups), Zhu Ziqing's writing style is forcefully modern and overwhelmingly direct. We hope you enjoy it.For those of you waiting for our next installment from Dream of the Red Chamber, just be patient. We'll be continuing the classic saga right where we left off in our next installment of this series.

barrister

said on December 19, 2008

We did this at university as well back in the days. Mind you, then it took us about two weeks and most of the class time was spent explaining the obvious or rifling through dictionaries. Good to see it again anyway, it's a touching story.Extensive reading is important to me. So keep up the publication of these pieces, please.

gnotella

said on December 19, 2008

Nice .

't would also be nice to have a reading of it to listen to..

Echo

said on December 19, 2008

@gnotella,

It is sth wrong with mp3 uploading. Fixing it. Thanks!

--Echo

echo@popupchinese.com

Short Stories

said on December 19, 2008

Hmmm must have had a problem uploading it last night- sorry about that everyone, it's up now at least. On to Film Friday....

ssgame

said on December 20, 2008

There seems to be a problem with the pdf too.

Short Stories

said on December 20, 2008

@ssgame - what problem are you having?

ssgame

said on December 20, 2008

I couldnt save the pdf to disc. The file was corrupted. Ive been able to print it off though, so no major harm done!

trevelyan

said on December 20, 2008

@ssgame - that's strange. Maybe it is a browser OS issue - will test out a few to see if we run into issues too.Looking at the PDF just now makes me think we should tweak it so the text fills the whole page for these stories. Doesn't make much sense to include space for the speaker in these stories.

veritas21

said on December 21, 2008

fantastic story!

yuehan

said on December 23, 2008

A question -- is 差使 pronounced chāshi or chāishi? I was under the impression that, when it referred to work, 差 was pronounced chāi (i.e., 出差, etc.).

Modern Chinese literature is brutally sad, isn't it...

Short Stories

said on December 23, 2008

Thanks for the catch John. I'd looked that up before and it is definitely chai1. Not sure how it slipped by, but it's fixed.

--dave

ZOE

said on July 1, 2009

Can anyone give me a summary of this story ? Im currently doing a project :D

barrister

said on July 2, 2009

@zoe - you should click through and read it with the popups. It's not actually very hard that way.

Short version: college student returns south on the occasion of his grandmother's death. His father has just lost his job and is short on cash, but insists on seeing his son off to the train back to Beijing. At the station he haggles for everything except for buying some tangerines the son expressed passing interest in. The son resents his father for his poverty, and begrudges the sacrifices his father is making for him. He pities his father for his clownish appearance and cries out of pity for himself.

At the end of the story the boy is a father himself and feels badly about the way he behaved. His father is nearing death. It's an unhappy ending all around, but fairly typically Chinese. We all end miserable and unhappy, etc.

edisonlyn

said on November 22, 2009

a short but touching story

Gail天堂的声音

said on November 23, 2009

@edisonlyn,

thanks. We have many other interesting stories here too. Enjoy!

npcr5

said on December 13, 2010

Why is 为了 given the pinyin wei2 le in the annotation? I thought it was wei4 le?

Echo

said on December 14, 2010

@npcr5,

Exactly! Already fixed. Thank you very much!

--Echo

echo@popupchinese.com

drummerboy

said on May 2, 2012

Question on this line: 哪知老境却如此颓唐. The popup explains 颓唐 as bald, however Pleco translates it as dejected/dispirited, which seems quite fitting in this context. Just curious which is correct? Thanks

amber

said on May 2, 2012

@drummerboy, 颓唐 has two meanings, first one is 'dejected/dispirited', the second is 'to decline or wane (in wealth and position)'. Here the second one is better.--Amberamber@popupchinese.com

Echo

said on May 2, 2012

@drummerboy,对,第一种情况也可以说“颓废”。--Echoecho@popupchinese.com

MAC.JAMIE

said on October 11, 2013

颓 does this word mean bald?

Grace Qi

said on October 11, 2013

Hi MAC.JAMIE,颓 means "dilapidated" as an adjective or "flow down" as a verb. The word "秃(tu1)" means bald. - Grace

MAC.JAMIE

said on October 11, 2013

Thanks, I expect you know that dilapidated can only refer to objects and generally houses; the colloquial expression is 'run-down' but you CAN use 'run-down' to describe a person.So would the best translation or reflection of the Chinese be ' run-down and bald?'Is that the idea?

MAC.JAMIE

said on October 11, 2013

In other words, the father lacks his former spirit and energy or elan, and is bald.

MAC.JAMIE

said on October 11, 2013

Anyway, thank you, I think I got it!!